Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent an innovative approach to targeted cancer therapy, delivering highly potent cytotoxic payloads directly to tumor cells while achieving a balance of efficacy and safety that is difficult for conventional chemotherapy or monoclonal antibody therapy alone. The ADC mechanism of action involves multiple coordinated steps, including specific antibody recognition of tumor antigens, cellular internalization, linker cleavage, and payload release, with each step directly influencing the antitumor activity and toxicity profile.

A thorough understanding of ADC mechanisms is essential for optimizing ADC design, improving therapeutic indices, and addressing resistance challenges, as well as providing both theoretical and practical guidance for developing new, potent, and controllable ADCs. This article systematically explores ADC's precise tumor-killing mechanisms from multiple perspectives, including molecular design, intracellular processing, pharmacokinetics, and clinical application, helping researchers and drug developers gain a comprehensive understanding of ADC functional characteristics and design principles.

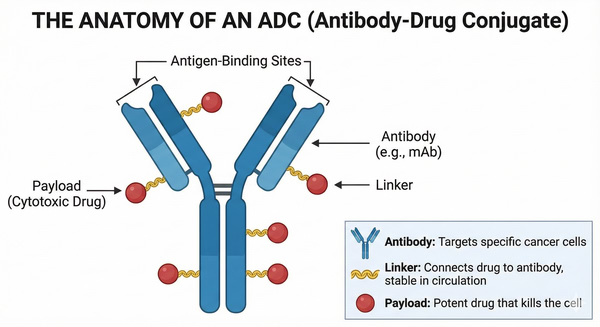

ADCs are targeted biologics that link a monoclonal antibody against a tumor-associated antigen to a highly potent cytotoxic drug via a chemical linker. The core components of ADCs include a highly specific monoclonal antibody, a stable linker, and an extremely potent cytotoxic payload. The antibody component recognizes and binds to tumor cell–specific antigens, the linker must remain stable in circulation to prevent premature drug release, and the cytotoxic payload is typically potent enough to induce cell death at nanomolar or even picomolar concentrations. This design allows ADCs to combine the targeting specificity of antibodies with the potent killing effect of chemotherapy, significantly enhancing the therapeutic index while reducing damage to normal tissues.

An ADC consists of a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes tumor antigens, a chemical linker, and a potent cytotoxic payload. Most ADC antibodies are of the IgG1 subclass to maximize circulating stability and immune effector functions. An ideal ADC typically includes a monoclonal antibody with high tumor-antigen specificity, a linker that is stable in plasma but cleavable inside target cells, and an extremely potent cytotoxic drug. The antibody targets the ADC to cancer cells, the linker maintains stability during systemic circulation until reaching the tumor, and the cytotoxic payload executes the lethal effect by interacting with intracellular targets such as microtubules or DNA, ultimately triggering apoptosis.

Fig. 1. Structure of an ADC showing antibody, linker, and cytotoxic payload bound to a cancer cell antigen (BOC Sciences Authorized).

Fig. 1. Structure of an ADC showing antibody, linker, and cytotoxic payload bound to a cancer cell antigen (BOC Sciences Authorized).

ADCs provide higher specificity and safety compared with traditional chemotherapy. Conventional chemotherapeutic drugs lack tumor specificity and often damage healthy cells during systemic distribution, resulting in severe side effects. In contrast, ADCs exploit the targeting ability of antibodies to deliver highly toxic drugs specifically to antigen-positive tumor cells, achieving potent cytotoxicity at low doses while sparing normal tissues.

Compared with monoclonal antibody therapy, ADCs enhance tumor-killing capability by conjugating a potent payload: while monoclonal antibodies mainly act through ADCC or signaling blockade and often cannot directly kill malignant cells, ADCs combine antibody targeting with highly toxic chemotherapeutic agents, overcoming the limited cytotoxic effect of antibodies and enabling effective tumor cell elimination even when target expression is low.

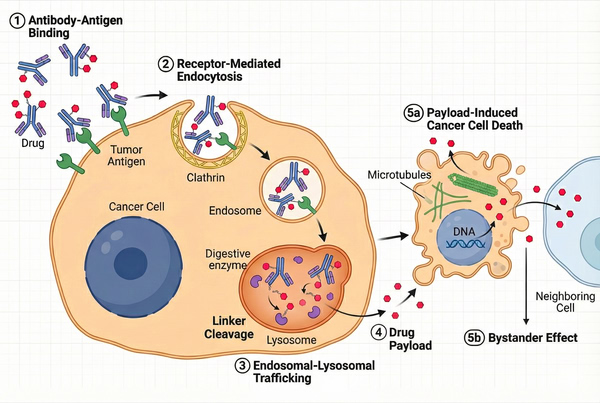

The ADC mechanism of action involves multiple consecutive steps: (1) antibody–antigen binding; (2) receptor-mediated internalization; (3) lysosomal linker cleavage and payload release; (4) cytotoxic payload–induced cell death; (5) bystander killing in tumors with heterogeneous antigen expression. Upon reaching the tumor site, the antibody portion of the ADC first recognizes and binds specific antigens on the tumor cell surface.

The ADC–antigen complex is then internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis and transported to the endosome–lysosome system. In the acidic, protease-rich lysosomal environment, the ADC linker is cleaved or the ADC is degraded, releasing the cytotoxic payload. The released drug molecules penetrate the cytosol or enter the nucleus, bind intracellular targets (e.g., microtubules or DNA), and induce apoptosis. Some membrane-permeable payloads can diffuse to neighboring antigen-negative tumor cells, generating a bystander effect that enhances ADC activity in tumors with heterogeneous antigen expression.

Fig. 2. Step-by-step mechanism of action of an ADC, from antigen binding to intracellular payload release and cancer cell death (BOC Sciences Authorized).

Fig. 2. Step-by-step mechanism of action of an ADC, from antigen binding to intracellular payload release and cancer cell death (BOC Sciences Authorized).

The first step of ADC action is the antibody-mediated recognition and binding to specific antigens on the tumor cell surface. This interaction is highly specific, typically designed against antigens overexpressed on tumor cells (e.g., HER2, CD30, CD22). Successful binding is a prerequisite for ADC efficacy: only after accurately recognizing and firmly binding to the target antigen can the ADC be internalized by tumor cells and initiate subsequent cytotoxic mechanisms.

After binding, the ADC–antigen complex triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis. The ADC is internalized into endosomes, which then fuse with lysosomes. This process translocates the ADC from the cell surface into the acidic endosome/lysosome compartment, preparing for drug release. The rate of internalization and trafficking depends on the target antigen's degradation and recycling properties: rapidly degraded antigens accelerate ADC delivery to lysosomes, whereas slow-cycling antigens may reduce intracellular transport efficiency.

The acidic lysosomal environment and various proteases (e.g., cathepsins, peptidases) play a critical role in linker cleavage. For cleavable linkers (e.g., Val-Cit, Phe-Lys), peptide bonds are enzymatically cleaved in lysosomes, releasing free drug molecules. For non-cleavable linkers (e.g., stable disulfide or non-degradable chemical bonds), antibody degradation is required to release payload molecules that retain a small linker fragment. The resulting payload, either free or linker-bound, then crosses the lysosomal membrane to enter the cytosol and exert its cytotoxic effect.

The released cytotoxic payload targets critical intracellular molecules, inducing apoptosis. Most ADC payloads are microtubule inhibitors or DNA-damaging agents, capable of arresting cell division or causing irreparable genetic damage. For example, microtubule inhibitors prevent tubulin polymerization, leading to mitotic arrest and apoptosis, whereas DNA-damaging agents trigger apoptotic pathways by crosslinking or cleaving DNA. These potent drugs can induce cell death at sub-nanomolar concentrations, greatly enhancing the ADC's tumor-killing potency.

In tumors with heterogeneous antigen expression, some released payload molecules can diffuse across cell membranes to neighboring antigen-negative cells, continuing to exert cytotoxic effects. This bystander effect broadens ADC therapeutic coverage, allowing effective treatment even in microenvironments with uneven target antigen distribution or antigen-negative tumor cells. Certain payloads, such as MMAE, are naturally membrane-permeable and readily generate a bystander effect, whereas less permeable payloads primarily act within target cells.

The ultimate efficacy of ADCs is influenced by multiple factors, including target antigen expression levels, linker stability and cleavage mechanism, cytotoxic payload potency and intracellular target, and drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR).

Selecting the appropriate target antigen is fundamental for ADC success: high and tumor-specific expression ensures preferential ADC uptake by cancer cells, maximizing local drug efficacy while minimizing off-target exposure. Intratumoral antigen heterogeneity or downregulation can reduce ADC binding and efficacy. For example, prolonged treatment may induce tumor cells to downregulate target expression through genetic regulation or mutation, a common clinical resistance mechanism. Antigen selection must also consider internalization capability: rapidly internalizing antigens facilitate ADC lysosomal delivery, whereas slow internalization or peripheral antigen expression may limit intracellular drug delivery efficiency.

Linker design directly determines ADC stability and release behavior in vivo. Highly stable linkers reduce nonspecific cleavage in circulation, limiting free drug exposure, whereas labile linkers rapidly release payloads upon reaching tumor cells, enhancing efficacy. Common cleavage mechanisms include enzymatic hydrolysis (e.g., lysosomal cathepsin-mediated peptide cleavage), chemical cleavage under acidic conditions, and disulfide reduction. Non-cleavable linkers require complete ADC degradation to release payloads, offering higher plasma stability but relying on intact intracellular processing.

The potency and intracellular target of the cytotoxic payload also directly affect ADC activity. Payloads are typically highly potent agents, such as anti-microtubule drugs or DNA-damaging compounds, capable of killing cells at very low concentrations. For example, auristatins and maytansinoids exert sub-nanomolar toxicity by rapidly inhibiting microtubule polymerization, whereas topoisomerase I inhibitors (e.g., SN-38, deruxtecan derivatives) trigger apoptosis by disrupting DNA replication. Payload selection must balance potency and controllability: overly toxic drugs risk off-target toxicity, whereas weaker agents require higher DAR or optimized targets to achieve efficacy.

The DAR is another critical parameter in ADC design. Higher DAR increases the number of drug molecules per antibody, generally enhancing tumor cell killing; however, excessively high DAR may increase hydrophobicity and aggregation risk, affecting stability and safety. Studies show that in tumors with low target expression, increasing DAR from 3.5 to 8.0 significantly enhances tumor-killing activity. Therefore, ADC preparation requires precise chemical or engineering control of DAR to balance efficacy and drug properties.

The clinically approved ADC payloads can be broadly categorized based on their cellular targets and mechanisms of action. Representative payload classes are described below:

This is the most widely used payload class in clinical ADCs. These drugs bind to tubulin and prevent microtubule polymerization, causing mitotic arrest and apoptosis. Common examples include auristatin derivatives MMAE/MMAF and maytansinoid derivatives DM1/DM4. For instance, DM1 effectively binds microtubules to block their function, while MMAE possesses strong cell permeability, enabling a bystander effect outside the targeted cell and expanding the therapeutic coverage.

These payloads induce cell death by directly cleaving or crosslinking DNA strands. Calicheamicin, for example, causes double-strand DNA breaks and was previously used in Mylotarg®. Pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers crosslink DNA within nucleosomes, resulting in irreparable genomic damage. DNA-damaging payloads have shown high efficacy in tumors with very high antigen expression.

Topoisomerase I inhibitors have recently emerged as ADC payloads. Typical representatives include SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, and deruxtecan (DXd) derivatives. SN-38 is used in Sacituzumab govitecan (a TROP2-targeting ADC), employing an enzymatically cleavable linker to release SN-38 in the low-pH lysosomal environment. Deruxtecan-based payloads are more potent than irinotecan and are used in multiple advanced tumor ADCs, such as Enhertu® (T-DXd) and Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd). These ADCs typically utilize protease-cleavable peptide linkers to release highly potent topoisomerase I inhibitors in lysosomes.

Discover our comprehensive portfolio of highly potent ADC payloads, including microtubule inhibitors, DNA-damaging agents, and topoisomerase inhibitors. Designed for optimal cytotoxicity, linker compatibility, and ADC development readiness across research and preclinical applications.

The antitumor activity of ADCs largely depends on whether they require target antigen–mediated internalization to release the drug. Understanding internalization-dependent versus non-internalizing mechanisms helps clarify their applicability and therapeutic potential under different tumor biology and microenvironment conditions.

The majority of ADCs rely on antibody-mediated internalization to release their payloads. After antibody binding to the antigen, the ADC is internalized and processed in lysosomes. In this internalization-dependent mechanism, linker cleavage or ADC degradation occurs primarily in the endosome–lysosome system.

For example, cathepsin-cleavable Val-Cit linkers are hydrolyzed by lysosomal cathepsins to release free drug. Non-cleavable linkers require antibody degradation to liberate the payload. This mechanism ensures that the cytotoxic payload is mainly activated within target cells, significantly reducing off-target exposure and systemic toxicity.

In contrast, non-internalizing ADCs are an emerging strategy that does not rely on cellular internalization. These ADCs target non-cellular components of the tumor microenvironment, such as the extracellular matrix or tumor neovasculature. The linkers are sensitive to tumor-specific enzymes or environmental conditions.

In the tumor region, the linker is cleaved by matrix proteases or acidic conditions, releasing diffusible cytotoxic drugs extracellularly, which can kill nearby tumor cells. This mechanism is suitable for tumors with suboptimal antigen expression or limited ADC uptake, providing an alternative approach to delivering lethal payloads.

ADC efficacy depends not only on target binding and payload release but also on pharmacokinetics and intracellular processing. Understanding ADC stability in circulation, tissue distribution, and endosome–lysosome trafficking is critical for optimizing efficacy, safety, and dosing strategies.

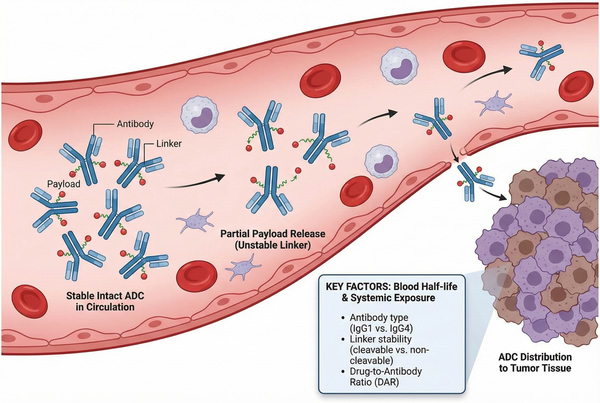

The circulating stability and systemic exposure of ADCs determine therapeutic effect and safety. ADC plasma half-lives are typically similar to their antibody carriers, lasting several days to weeks, offering a clear advantage over free small-molecule drugs. Linker stability is crucial for maintaining ADC integrity in blood; stable linkers reduce premature payload release, lowering off-target toxicity. ADCs exist in multiple measurable forms in vivo (e.g., conjugated ADC, free payload, free antibody), and their pharmacokinetic behaviors collectively impact efficacy and toxicity. For instance, lysosomal enzymes accelerate payload release within tumor cells, while stable ADCs in peripheral blood extend circulation time for optimal tumor targeting.

Fig. 3. Circulation stability and systemic exposure of ADCs (BOC Sciences Authorized).

Fig. 3. Circulation stability and systemic exposure of ADCs (BOC Sciences Authorized).

Intracellular trafficking and drug processing are critical for ADC activity. After endocytosis into early endosomes, ADCs usually fuse with newly formed lysosomes. The acidic lysosomal environment and proteolytic enzymes degrade the antibody and trigger linker cleavage. Cleavable linkers are enzymatically cut in lysosomes, releasing the drug via self-immolative mechanisms. Non-cleavable linkers rely on complete antibody degradation to release payloads. Studies also indicate that neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated recycling in early endosomes can return some ADCs to the cell surface, potentially reducing lysosomal cleavage and drug release, and may contribute to ADC resistance.

As with all cancer therapies, ADCs face clinical resistance, impacting mechanism and efficacy. Major resistance mechanisms include:

A deep understanding of ADC mechanisms guides clinical development and drug design. Each ADC component should be designed to complement its mechanism, balancing efficacy and safety. Target selection requires consideration of expression specificity and level: highly expressed tumor-restricted antigens improve efficacy while reducing off-target effects, whereas antigens present in normal tissue risk "on-target, off-tumor" toxicity. Linker design must balance plasma stability with tumor microenvironment cleavage: stable linkers minimize systemic leakage, while efficient cleavage in the tumor ensures therapeutic effect.

The mechanism of action also closely relates to the efficacy–toxicity profile. Although ADCs are precisely targeted, side effects can result from premature release in non-tumor tissues or expression of the target in normal cells. Highly potent payloads increase cytotoxicity but also carry risk if released uncontrolled. Clinical studies indicate adverse event timing and type are strongly linked to payload and target selection. Therefore, ADC design and clinical trials must consider the full mechanism to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing safety risks.

BOC Sciences has established an integrated service platform covering early ADC discovery, process development, and cGMP manufacturing, leveraging mature chemical synthesis, bioconjugation, and analytical characterization capabilities. Centered on "mechanism-driven design and "manufacturability-oriented development, we help clients maximize ADC efficacy and mechanistic potential while minimizing risks in tech transfer, scale-up, and regulatory submission, accelerating clinical and commercial progression.

From cytotoxins to linkers, explore our cutting-edge products for your ADC project.

| Catalog | Name | CAS | Price |

| BADC-00045 | Auristatin F | 163768-50-1 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00309 | MMAD | 203849-91-6 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00357 | Ansamitocin P-3 | 66584-72-3 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00372 | SPDP | 68181-17-9 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-01135 | Fmoc-N-amido-PEG4-propionic acid | 557756-85-1 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00933 | DBCO-NHS ester | 1353016-71-3 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00016 | Vat-Cit-PAB-MMAD | 1415329-13-3 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00022 | DM3-SMe | 796073-70-6 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00013 | MC-Val-Cit-PAB-MMAF | 863971-17-9 | Bulk Inquiry |

| BADC-00942 | Fmoc-Val-Ala-PAB-OH | 1394238-91-5 | Bulk Inquiry |

Explore our advanced tools and expertise for next-generation ADC research and development.

Potent cytotoxins designed for targeted antibody-drug conjugate therapy.

Stable, selective linkers enabling precise drug release in ADCs.

Integrated payload-linker solutions for efficient and targeted ADC delivery.

Targeted therapeutics combining antibodies with cytotoxic drugs for precision treatment.